What is the Dunning-Kruger effect?

Some years ago, there was a lot of finger-pointing about a prominent politician’s level of intelligence and ability to lead a country. Many people had cited the Dunning-Kruger effect. It seems that we collectively understood it to mean that an unintelligent person is unaware of their own low level of intelligence.

But let’s look at what this actually is.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias (a type of “illusory superiority”) in which people wrongly overestimate their knowledge or ability in a specific area. This tends to occur because a lack of self-awareness prevents them from accurately assessing their own skills.

The effect was first identified by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in 1999. They conducted a series of studies in which they asked participants to rate their own abilities in various areas, such as grammar, logic, and humour. They found that the people who performed the worst on these tests were also the most likely to overestimate their abilities.

A recent study has questioned the validity of Dunning and Kruger’s conclusion, and when they restudied the data, they found that the data shows that all of us overestimate our competence, not only those of us with low competence.

If we were to stop and think about it, we would most likely see that we have all fallen prey to this bias at one point or another whether through our own lack of self-awareness of our own abilities. Or, we may have witnessed it in a colleague who constantly believes they have all the answers.

But let’s be clear: the Dunning-Kruger effect is not about being intelligent or not. It is much more about emotional intelligence and self-awareness.

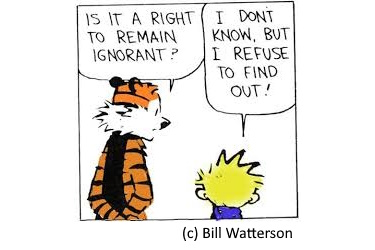

One of the dynamics we are aware of is our innate need for certainty. The brain does not like to not know. It wants to know “I can” or “I can’t”. It’s much harder to stay with “maybe”, “I don’t know if I can learn” and other states of ambiguity. It would much rather decide, one way (I can!) or the other (I can’t) than be in this vague in-between place. This need for certainty, coupled with our desire to be good, leads us to jump to a conclusion about our competence.

Let’s dare to look at ourselves

Let’s be honest that we all fall into the trap of this cognitive bias and see when it might be happening:

- When have you read about a concept or learned a skill and immediately thought that you knew exactly what it was all about?

- Are you aware of when your brain says, “of course you can do that!” when in fact, maybe you can’t?

- When have you jumped into something thinking you knew what you were doing and then you found out you weren’t quite the expert you thought?

- How easy is it to suspend your need for certainty so you can stay in a learning mindset?

Many people who work towards mastery will say: the more I learn, the more I know that I have so much more to learn.

This is a normal human dynamic. And, the Dunning-Kruger effect, while also a natural human response, has the opposite sentiment.

When introduced to a new concept or skill, we naturally compare that to something we already know. When we find a similar concept from our past, it’s easy to assume that these two concepts are the same thing. Then, we lean into our expertise of our familiar concept (which provides us with a feeling of certainty) instead of paying attention to the differences. Then our curiosity about the new skill is shut down, our learning diminishes, as does the possibility of truly becoming competent with this new skill. And there we are, caught in Dunning Kruger’s cognitive bias.

What can we do instead?

- Be humble. It’s important to remember that you don’t know everything. Don’t be afraid to admit when you’re wrong or when you need help.

- Be a hungry learner (look into “beginner’s mind”) and keep looking for what’s new in a topic rather than what you already know.

- Be open to feedback. One of the best ways to learn about your own weaknesses is to solicit feedback from others. Ask your friends, family, and colleagues for honest feedback on your skills and abilities.

- Be confident in what you do, but also ask yourself, what can I learn and how can I keep learning about this topic.

- Become aware of your need for certainty, know that it’s just your survival brain having its say, acknowledge it and try to set it aside – reassure yourself that it is OK to not know.

What is Rewired to Relate?

Rewired to Relate offers insights about how certainty and other factors influence our behaviour in a multitude of ways.

Attend one of our short free webinars to learn more about it: What is Rewired to Relate

more info